India’s silent tree crisis on farmland: The hidden loss of trees and its impact

India is losing millions of farmland trees at an alarming rate, especially in regions like Indore. This silent crisis affects climate resilience, crop health, and biodiversity. Here's why we need action.

India’s Silent Tree Crisis on Farmland

If you stand in many fields around Indore today, you’ll notice something missing. The shade. The old trees. The green corners that once gave life to the farms. A lone tree stands here and there, but the landscape feels emptier than before. It is a silent change, but a serious one.

If you stand in many fields around Indore today, you’ll notice something missing. The shade. The old trees. The green corners that once gave life to the farms. A lone tree stands here and there, but the landscape feels emptier than before. It is a silent change, but a serious one.

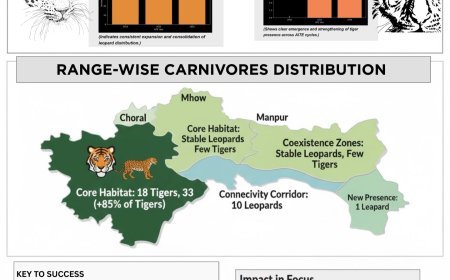

A recent scientific study confirms what farmers have been saying quietly: India is losing its farmland trees at a worrying pace. Researchers from the University of Copenhagen mapped about 60 crore individual farm trees across the country. They found that almost 11 percent of the big trees present in 2010 had disappeared by 2018, and another 50 lakh trees vanished between 2018 and 2022. Indore, along with several regions in Maharashtra and Telangana, was identified as a hotspot for tree loss. Despite these huge numbers, most of us don’t even realize the decline is happening.

Why it matters: The role of farm trees

This loss is significant because most of India’s trees grow outside forests. Only 20 percent of the country is officially forest land, while 56 percent is farmland. This means most of India’s trees are standing on fields, village lands, and farm boundaries. These trees cool the soil, reduce heat, hold moisture, and support pollinators like birds and bees. They act as natural climate defenders. When they disappear, the land becomes weaker, more exposed to heatwaves and unpredictable rainfall.

The invisible loss: Why farmland trees aren’t counted

Here’s the strange part: Most of these trees are not even recorded in government records. The Forest Survey of India only counts trees in patches larger than one hectare with more than 10 percent canopy cover. Lone trees don’t count. Revenue records also ignore individual trees. So, when a farmer cuts down a neem or babool, it’s as if the tree never existed. This is why the crisis has remained hidden for so long.

On the ground in Indore: Why are these trees disappearing?

To understand this crisis, just listen to the farmers around Mhow, Sanwer, and Manpur. Most say the same thing: trees get in the way. Modern farming uses tractors, tillers, and combine harvesters. A large tree in the middle of a field blocks movement and reduces the area available for crops. With high input costs and shrinking landholdings, farmers feel every square meter must be productive.

Then there’s the market pressure. Indore’s Guru Nanak Timber Market, one of central India’s largest timber hubs, buys wood from villages daily. Farmers know that timber buyers offer quick cash, which makes cutting trees tempting. Some even cut large trunks into small firewood bundles, which are easier to transport. Once chopped into pieces, the wood disappears into the firewood market without a trace.

Nearby, small factories burn farm wood as fuel, creating a steady demand for trees—quiet, constant, and unrecorded. Urbanization compounds the problem. As suburbs around Indore expand, farmland is converted into plots, commercial spaces, and farmhouses. Old trees are removed to “clean up” the land before sale.

The bigger picture: What’s lost when a tree is gone?

Every lost tree has an impact. A single mature tree may seem small compared to a vast field, but it plays multiple crucial roles. Its deep roots support crops during dry spells, its shade protects soil from overheating, and its leaves enrich the land. Birds and pollinators use it for shelter and food. Losing these trees is like losing our natural insurance system just as climate change is making weather patterns more erratic.

What can be done? A national farmland tree policy

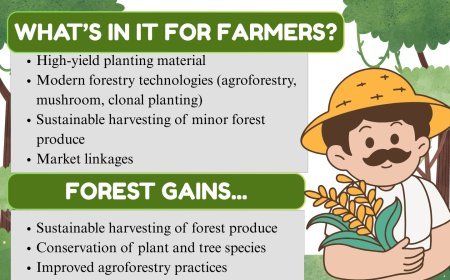

These trends point to the urgent need for a National Farmland Tree Policy. First, we must create a simple registry to track farm trees, ensuring they’re counted. If a tree is felled, it should not disappear unnoticed. Farmers should be incentivized or certified for preserving old trees. Rules for felling and transporting wood must be simplified and standardized across states. Wood markets and factories should record how much farm wood they buy to reduce hidden removals.

Most importantly, we must start viewing farmland trees as climate assets, not obstacles. They help crops survive heat, protect villages during storms, and maintain rural landscapes.

Conclusion: Saving trees, saving farms

The next time you pass a field and see an old tree standing tall, remember this: it may look lonely, but it is doing the work of an entire climate system. Saving it might just save the farm around it.

By Pradeep Mishra, Indian Forest Service (IFS), currently serving as DFO Indore