Ethical dilemma of the Harsoala leopard rescue: A mother, cubs, and compassion

Discover the complex ethical and ecological challenges faced during the Harsoala leopard rescue. A mother, two cubs, and a wire trap — this case explores the tough decisions in wildlife conservation.

A mother, two cubs, and a wire trap: The ethical dilemma behind the Harsoala leopard rescue

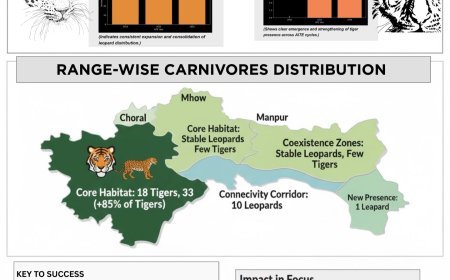

Wildlife rescues rarely follow a straightforward path. The recent leopard rescue case from Harsola village in the Mhow Range of Indore Forest Division, however, stretched every boundary—emotional, ethical, and ecological. What began as a routine rescue turned into a complex moral dilemma that no rulebook could prepare one for.

Wildlife rescues rarely follow a straightforward path. The recent leopard rescue case from Harsola village in the Mhow Range of Indore Forest Division, however, stretched every boundary—emotional, ethical, and ecological. What began as a routine rescue turned into a complex moral dilemma that no rulebook could prepare one for.

On November 3, a five-year-old female leopard was found trapped in a wire snare on revenue land. In her desperate struggle to free herself, she severely injured her left hind leg. The rescue team swiftly tranquilized the animal and transferred her to Indore Zoo, where an X-ray revealed a fracture in the lower part of the leg. Despite applying a plaster, the leopard removed it within days, licking her wound, further complicating her recovery.

But the story doesn’t end there.

A new crisis: Two cubs alone

On November 11, a group of children spotted two leopard cubs—barely three months old—wandering alone near a rocky patch. Alarmed, the children alerted the village, and the police informed the Forest Department. The rescue team scoured the area for hours, hoping to locate the mother. But despite their efforts, no adult leopard appeared.

This posed a crucial question: Should the cubs be rescued, or should they be left to wait for the mother to return?

The decision was a delicate one. If the mother was alive, rescuing the cubs could risk breaking up the family. But if she was dead, still trapped, or in a condition that prevented her from returning, the cubs were at immediate risk. It was possible that the injured leopard the team had rescued earlier was the very mother of the cubs.

The decision to rescue the cubs

Guided by advice from the Chief Wildlife Warden of Madhya Pradesh and the Chief Conservator of Forests, the team decided to bring the cubs to Indore Zoo. The decision wasn’t made out of certainty, but rather out of concern for the cubs' safety and survival.

Now, a new dilemma emerged: Should the cubs be allowed near the injured leopard? Opinions were divided. Some experts feared the adult leopard might reject or harm the cubs due to the human scent, or that the stress of the encounter could worsen her injury. Others suggested there were rare cases where leopards have accepted cubs after brief human handling. Yet others questioned whether the cubs' mother had even survived at all, given that cubs rarely survive without maternal care for long.

Genetic tests could provide clarity, but the team moved forward, guided by what they knew: these cubs were too young to be released into the wild. Their survival instincts were still underdeveloped, and prolonged captivity could lead to human imprinting, making future reintroduction into the wild even more difficult.

The paradox of wildlife rescue

This is the paradox of wildlife rescue: saving a life is often easier than saving its wildness.

In Harsola, the daily patrolling continues. Teams monitor the area, look for tracks, and listen for calls, hoping for signs of the mother or any other leopard that could shape future decisions. The Harsoala case underscores that wildlife conservation is not about clear answers. It’s about making responsible decisions in a world where every choice holds consequences and every delay risks a life.

As forest officers, we act with sincerity, driven by science, empathy, and the humility to accept that nature, not us, writes the final chapter.

For now, we can only hope for the best outcome: a healed mother, growing cubs, and a forest that welcomes them back home.

By Pradeep Mishra, Indian Forest Service (IFS), currently serving as DFO Indore